This post marks the conclusion of my series exploring the inns of Billinghay. Over the past few months, I’ve traced the histories of the Cross Keys, the Golden Cross, and the Coach & Horses—each a cornerstone in the life of our village. These public houses have not only served ale but also fostered community, witnessed generations, and reflected the changing face of Billinghay. Together, their stories offer a rich and revealing glimpse into the social and cultural fabric of our past.

Through my research, I’ve traced the lives of the men and women who kept these inns alive, and it has been a genuine delight to see how this journey has sparked memories among so many of you who have read my blogs. What I’ve come to discover is that these establishments were far more than places of refreshment—they were social anchors at the heart of the village. Each landlord and landlady brought their own story, and together their lives reveal Billinghay’s past: times of prosperity, periods of struggle, and the steady, inevitable change that reshaped village life over the decades. In exploring their histories, we reconnect not just with buildings, but with the people and the spirit of a community.

And so, for the final time, I turned my attention to The Mill Inn, situated on West Street, Billinghay—once known as Back Street. Researching this particular inn proved especially fascinating. Initially, it appeared to be less prominent than some of the village’s other public houses; however, the Mill Inn revealed itself to be well known and remembered, with a certain character all its own. Owned by the Soulby, Sons & Winch brewery, the inn had a rich and unexpected significance within the local community. Its close connection with the neighbouring mill, once central to Billinghay’s agricultural economy, illustrates just how interwoven these establishments were with local trades, livelihoods, and daily life.

The Story of the Mill Inn and Its Keepers

Transition to West Street

The Mill Inn once stood on what is now West Street. However, when the inn first appeared, around the 1880s, the street was known as Back Street, a name reflecting its position behind the main cluster of the village. By 1905, it had been renamed West Street. Ordnance Survey maps from 1887 depict the area in detail: a prominent mill just west of the village centre dominated the landscape, with footpaths that would later develop into Mill Lane and Back Street (West Street).

Location and Early Context

One of my first aims was to establish the exact location of The Mill Inn. Through talking to my Billinghay family, they were able to confirm the likely location, and their memories suggest it once stood at what is now the entrance to an industrial estate.

Present-Day Clues

The Mill Inn on West Street in Billinghay was situated opposite the Mill, owned by the South family, and was once central to local life. In 1881, John South was recorded in the census being a Miller and Baker. Its close proximity to the inn not only gave the establishment its name but also supplied much of its regular clientele. The mill ceased operation in 1935.

Even today, standing in that spot, you can still sense the echoes of its past—the shape of the lane, the view across the road, the quiet imprint of what once was. Directly opposite the inn stood the mill itself, now long vanished from the landscape. I remember the mill as a child—its stump a low, ivy-covered ruin along Mill Lane, slowly being reclaimed by time. Today, it is no more.

The Mill Inn and the mill were intimately connected—their histories running side by side. In their own modest way, they formed a small but vital hub of Billinghay’s working life, now surviving only in memory, photographs, and—thanks to one local artist—a single drawing.

The Mill Inn Keepers

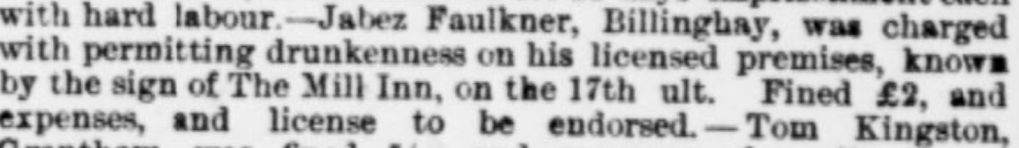

So now we turn to the innkeepers—for the story of The Mill Inn is, in many ways, about those who ran it. The earliest record I found appears in the Boston Independent & Lincolnshire Advertiser in 1881, when innkeeper Jabez Faulkner was charged with allowing drunkenness on his premises, then known by the sign of the Mill Inn. Jabez was fined £2, and his licence was endorsed.

Jabez Faulkner: Carrier and Early Ale Seller?

It is likely that Jabez Faulkner, known in Billinghay as a carrier, was also an early purveyor of ale, potentially operating informally from his own premises. This was a common start for many rural inns: individuals involved in trades such as carting, farming, or blacksmithing would offer refreshment—often homemade beer—to travellers, customers, or locals. Over time, these homes or workshops evolved into fully licensed establishments as demand grew. If Faulkner was indeed selling ale alongside his carrying business, it may mark the earliest phase in the development of what later became The Mill Inn. There are no other records until 1893.

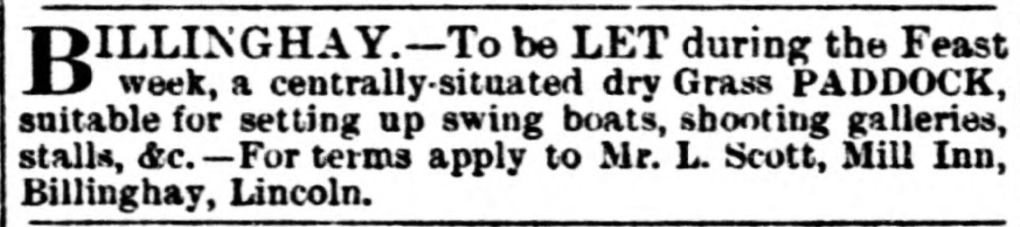

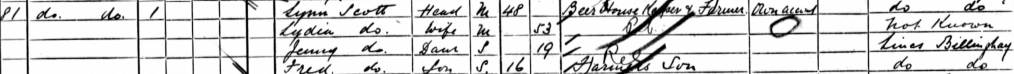

Lynn Scott 1893: Beerhouse Keeper and Farmer – In September 1893, an advertisement appeared in the Stamford Mercury offering a grass paddock in Billinghay “to be let during the Feast Week.” The paddock, promoted as suitable for fairground attractions such as swing boats, shooting galleries, and stalls.

The contact for arrangements was Mr. L. Scott of the Mill Inn, Billinghay, his full name being Lynn Scott, the Inn Keeper. Further research confirms that Robert and Lynn Scott were brothers.

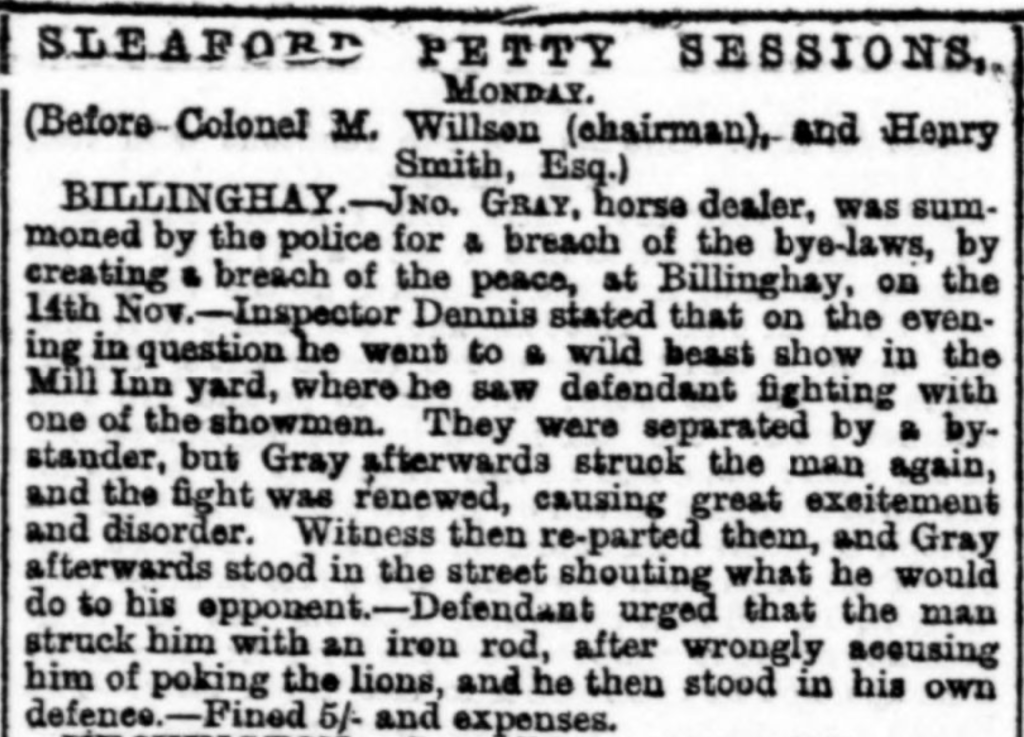

Trouble at The Mill Inn yard while the Wild Beast Show was on!

By the time of the 1901 census, Lynn Scott was recorded living on Back Street and was both a beer house keeper and a farmer. Back Street hosted farm workers and family alike, hinting at the dual economic role many rural publicans held: running both an inn and a smallholding. This dual occupation was typical in agricultural villages, where supplementary income was vital.

These articles confirm that the paddock at The Mill Inn was often used for sales, accommodating travelling circuses and was also available for use during the village feast in October.

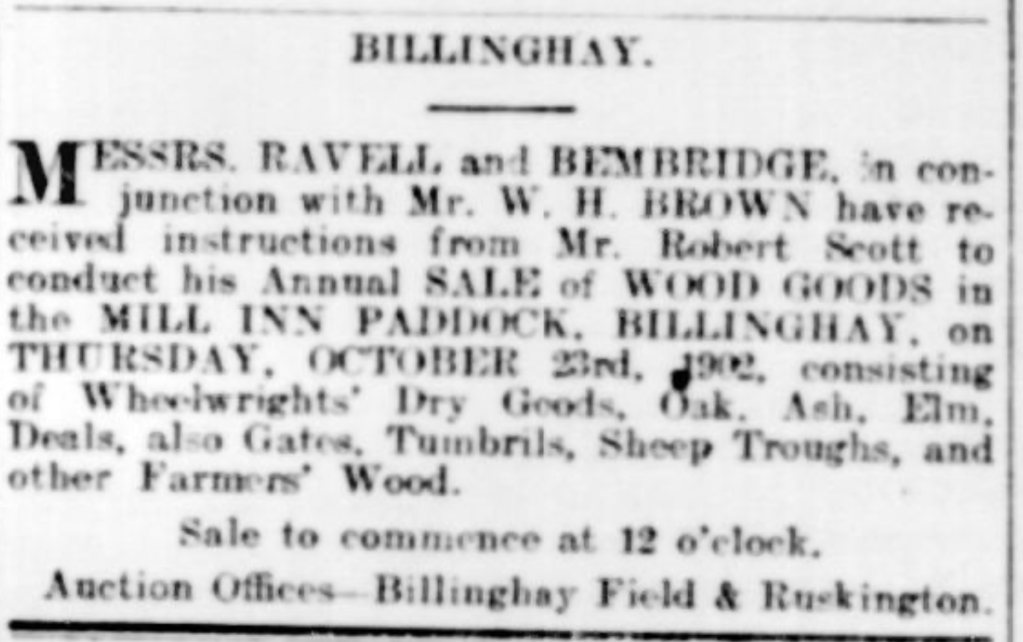

This newspaper article confirms that Robert Scott, a Timber merchant, was selling his timber in the Mill Inn Paddock, no doubt agreed by his brother Lynn.

Lynn Scott died in 1912. Unfortunately, there is a gap in the records until 1921, when the 1921 census lists John Henry Toulson as the innkeeper on West Street, working with his own account. He was living with his wife, Elizabeth, and their three children: Henry, Arthur, and Rhoda.

However, further newspaper research reveals that John Henry Toulson was serving as the innkeeper at The Mill Inn well before the 1921 census. He appears in local tribunal reports as early as 1917, listed as both a labourer and innkeeper of Billinghay, confirming his role during the wartime years.

Wartime Exemption and Community Presence.

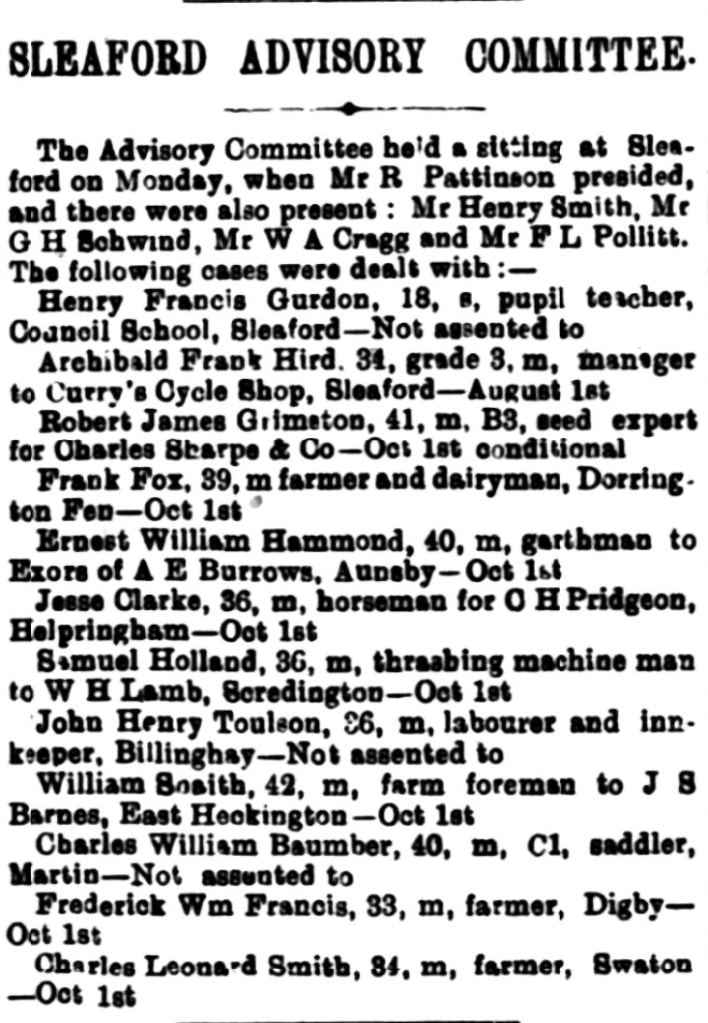

In April 1918, amid the final year of the First World War, John Henry Toulson appears in the Sleaford Gazette in connection with the Sleaford Advisory Committee. These committees were convened to consider applications for exemption from military service under the Military Service Acts, which had introduced conscription in Britain starting in 1916.

John Henry Toulson, at the time, described as a 36-year-old labourer and innkeeper of Billinghay, had applied for exemption. The committee, however, did not assent to his application, effectively rejecting his claim. This would have placed him at risk of being called up unless he appealed the decision or met other exemption criteria.

His appearance before the Advisory Committee offers a glimpse into the pressures faced by working men during wartime—especially those juggling civilian responsibilities like running a village inn. For John Toulson, The Mill Inn was not just a business but a livelihood for his family. Yet, in the eyes of the authorities, that role was not considered sufficient grounds for military exemption.

This also confirms that John Henry Toulson was actively running the Mill Inn by 1918—three years before his appearance in the 1921 census—and highlights the intersection of local history with national events, as the war reached even the quiet lanes of West Street, Billinghay.

However, this is only part of the story; there were many committee meetings held regarding the young men looking for an exemption to be conscripted into the war.

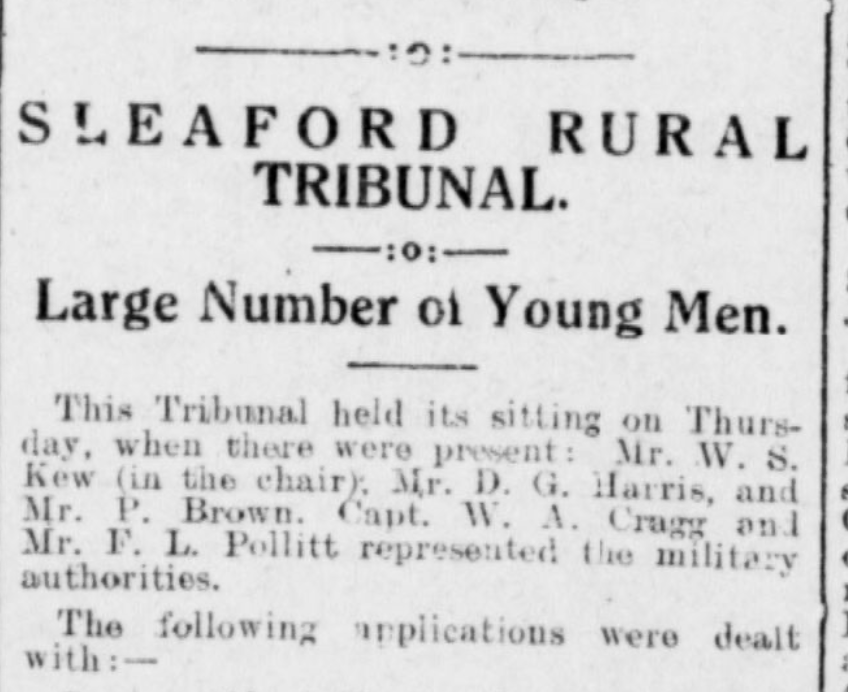

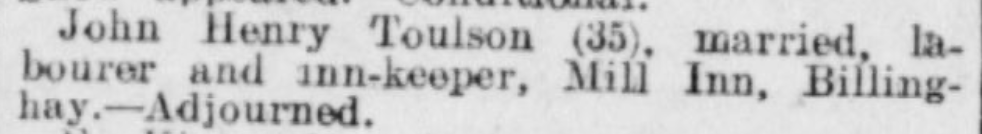

John Henry Toulson, innkeeper of the Mill Inn in Billinghay, appears more than once in local wartime records. In the Lincoln Leader and County Advertiser dated 24 February 1917, his case for military exemption was adjourned—suggesting an earlier attempt prior to the April 1918 decision by the Sleaford Advisory Committee, which ultimately refused his claim.

This sequence of records illustrates how Toulson—like many men in reserved occupations—faced increasing pressure as the war dragged on. As both a labourer and innkeeper, his dual role may not have been enough to justify exemption in the eyes of the tribunal, despite his position at the heart of Billinghay’s working life.

The case of John Henry Toulson highlights how wartime bureaucracy, personal circumstances, and shifting national priorities could all influence the fate of individuals during the First World War. Even with a rejected exemption, not every man necessarily ended up in uniform—particularly as the war drew to a close and the need for new recruits diminished.

The war’s reach into every corner of village life. Each young man’s experience was shaped not just by the battlefield, but by tribunals, family responsibilities, health, and community sentiment. These stories offer a poignant window into how global conflict played out in the most local and personal ways.

Post War

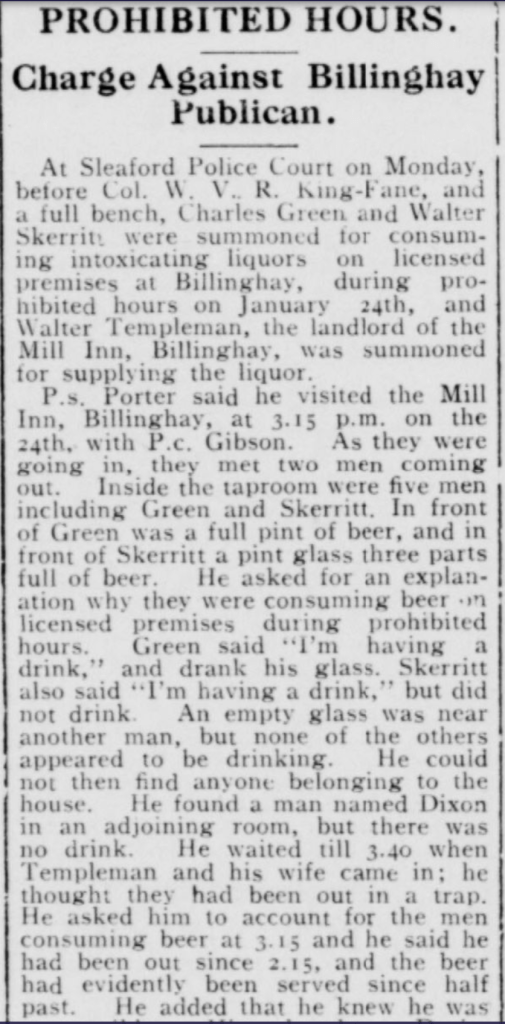

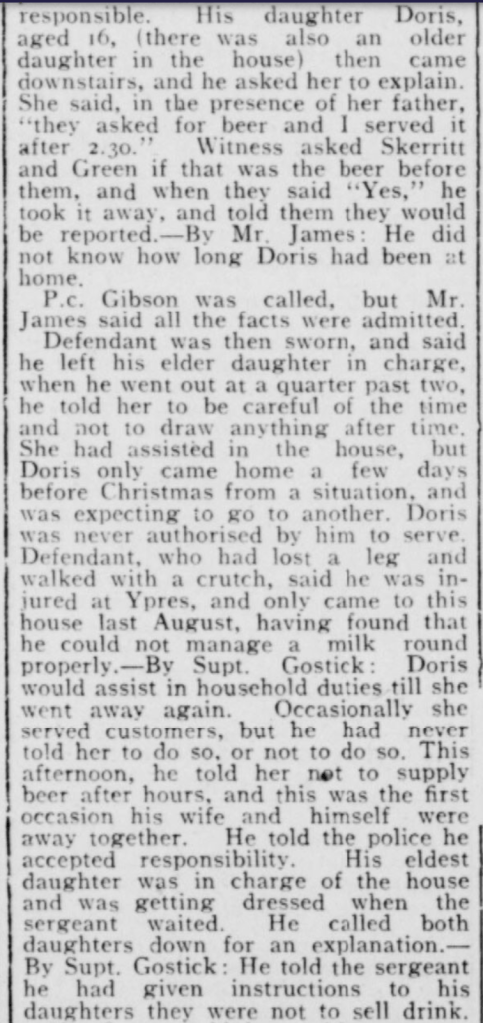

Eventually, the management of The Mill Inn changed, and by 1928, the innkeeper was named Walter Templeman. However, as trouble often surrounded The Mill Inn, Mr Templeman was no exception. Reported in the Lincoln Leader and County Advertiser, 4 Feb 1928

Walter Templeman was fortunate, as due to being injured in Ypres during WW1, his case was ultimately dismissed. Following this, Walter continued to run The Mill Inn. A series of newspaper articles confirms his active involvement in the local community through the inn he managed.

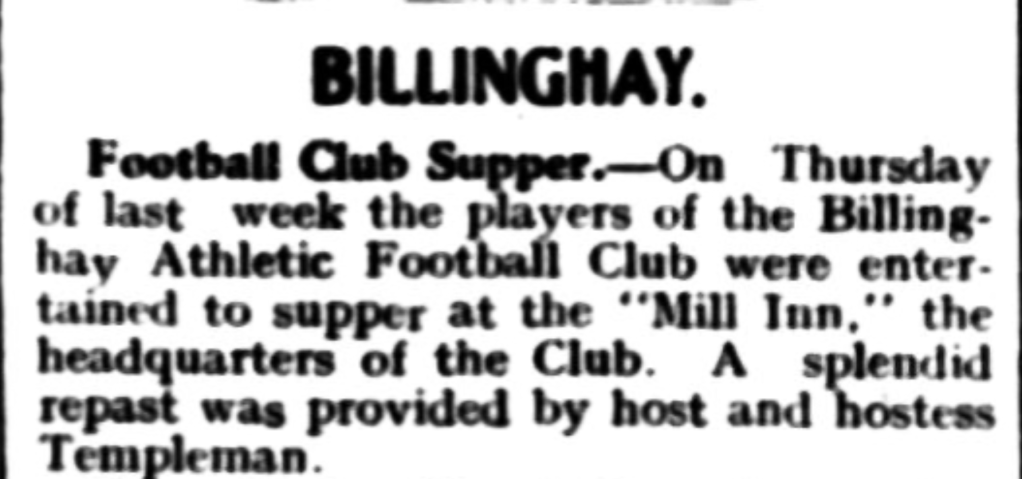

Football Club Suppers held at The Mill Inn.

Audrey Templeman, daughter of Walter Templeman – pictured in the Spalding Guardian 1939, as a maid to the elected beauty queen. Audrey is standing on the right of the picture.

Miss Audrey Templeman was supportive of her parents and organised fetes, as this newspaper article confirms. This also confirms the Templemans were still running The Mill Inn in 1941.

Walter William Templeman sadly died in September 1941 whilst still the innkeeper of The Mill Inn. His obituary was reported in the Boston Guardian.

Researching the history of the Mill Inn has at times been sketchy and fragmentary—but then came a striking headline in the Sleaford Gazette from 1947:

“Fish and Chips Beside the Alehouse”

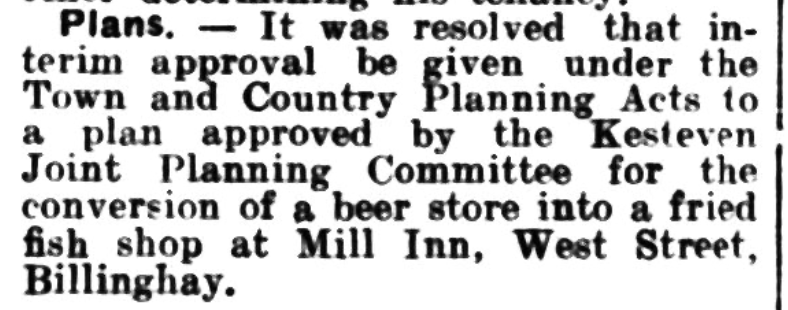

In a conversation with my cousin, it was recalled that a fish and chip shop once stood next to The Mill Inn in Billinghay. This memory is supported by a report in the Sleaford Gazette dated 14 March 1947, which noted that plans had been approved to convert the beer store adjacent to the Mill Inn into a fish and chip shop. This change reflects a post-war adaptation of the site, illustrating how village commerce and social life were beginning to shift in response to modern needs.

As traditional beer-houses adjusted to new economic realities, the addition of a fish and chip shop—an increasingly popular and affordable takeaway—demonstrates how premises once devoted solely to ale continued to serve the community in new and practical ways.

Thomas Hutchinson, mentioned in the following newspaper article, was the licensee up until Monday, 4 October 1954. I am unable to find a record of exactly when he first became the licensee. But we can assume it was after September 1941 and 1953.

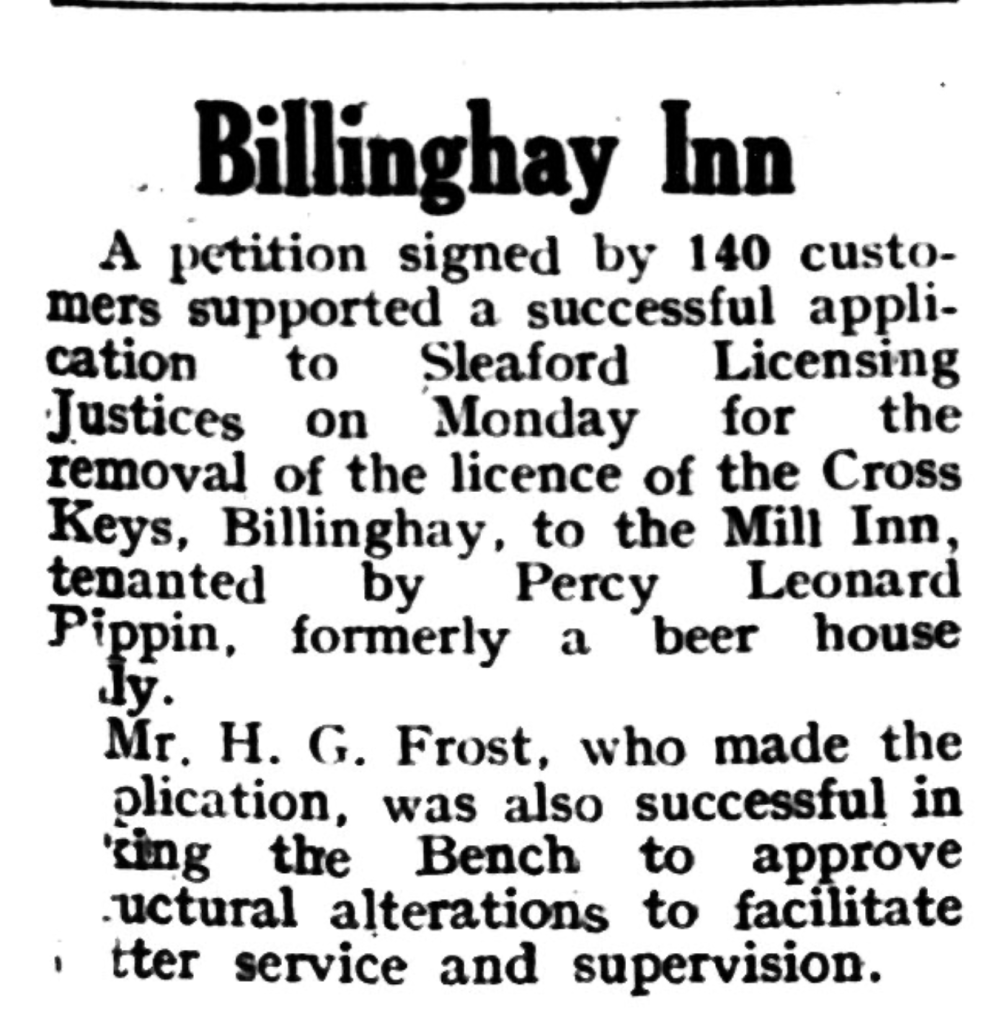

Percy Leonard Rippin was running The Mill Inn from 4 October 1954, as the Sleaford Gazette reports.

Leonard Percy Rippin – A Billinghay Man in War and Peace

Leonard Percy Rippin was born in Billinghay in 1910, a local man who would go on to serve his country during the Second World War. The 1911 Census records Leonard as a six-month-old infant, living on High Street, Billinghay, in the care of his grandparents. Like many in rural Lincolnshire, Leonard followed a life connected to the land. By the time of the 1939 Register, he was working as an Agricultural Straw and Hay Trusser—a skilled and physically demanding occupation vital to farming and livestock industries.

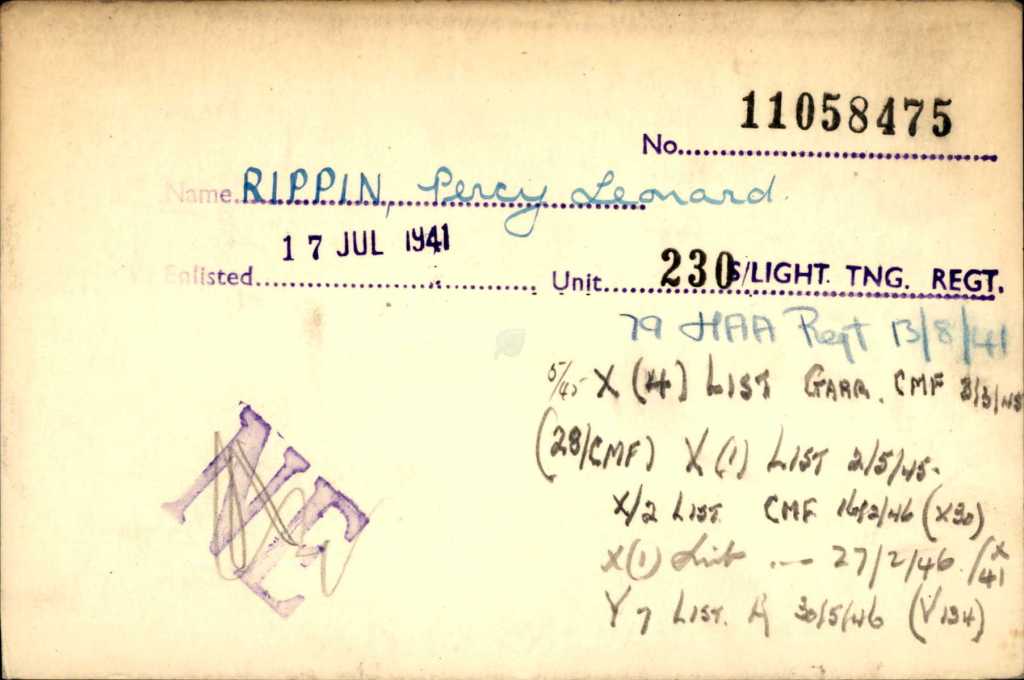

However, with the outbreak of World War II, Leonard answered the call to service. On 17 July 1941, he enlisted in the British Army, receiving the service number 11058475. He was initially posted to the 230th Light Training Regiment, Royal Artillery (230 L.TNG. REGT.), where new recruits were prepared for active service.

On 13 August 1941, he was transferred to: 79th Heavy Anti-Aircraft Regiment. This regiment was part of the Royal Artillery, specifically trained and equipped to defend against enemy aircraft using large-calibre anti-aircraft guns.

After returning home, Percy Leonard Rippon married Mable Sharp in 1947, and the couple settled back in Billinghay to raise a family. In 1954, Leonard and Mable Sharp took over the running of The Mill Inn, one of the village’s long-standing public houses. Their stewardship of the pub marked a new chapter in their lives—contributing not just to the local economy, but to the social heart of Billinghay. As publicans, they hosted village events, welcomed locals and visitors alike, and helped preserve a rural tradition of hospitality.

Following Mable’s death in December 1976, it is unclear whether Leonard continued to run The Mill Inn. By the time of his own passing eight years later on 7 December 1984, Leonard was no longer at the pub but living in the village. Both are remembered as lifelong members of the Billinghay community—figures who lived through war, peace, and change, and who left their mark quietly but meaningfully on village life.

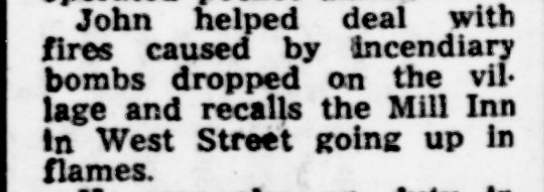

Blaze at the Mill Inn – Remembered by a Firefighter

An intriguing glimpse into Billinghay’s past appeared in the Sleaford Standard on 28 September 1973, in an article marking the retirement of veteran volunteer firefighter John Mablethorpe. In the piece, Mablethorpe reflected on the many incidents he had responded to over the years, including a particularly memorable one: a blaze at The Mill Inn. Though details in the excerpt are limited, the mention of this fire provides a rare and evocative insight into the later history of the inn, long after its heyday as a village hub.

Taking over the Mill Inn in 1954, Leonard and Mable were still there 20 years later.

A Lost Landmark Remembered in Ink

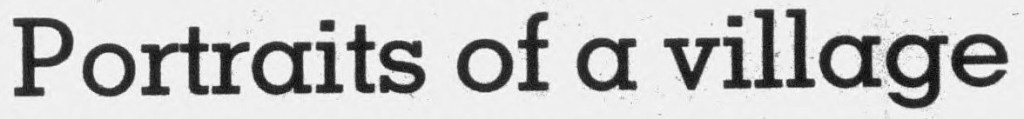

By 1992, the Mill Inn in Billinghay had become a derelict building—its windows dark, its doors long closed. Shortly after, it was demolished, and with it went a piece of the village’s social fabric. But thanks to a young local artist, Paul Marshall of Poplar Fen, we are lucky to have one last glimpse of the building before it vanished from the landscape.

This article in the Lincolnshire Echo, dated 3 November 1993, featured a detailed drawing of the Mill Inn, created by Paul as part of his project to record the buildings and street scenes of Billinghay. His work was to be displayed at a craft fair at Walcott Primary School later that month. The illustration captures the architecture and character of the pub—tiled roof, twin chimneys, and gabled windows—preserving it in memory if not in brick.

If this is the only surviving image of The Mill Inn, it’s a wonderful thing that Paul managed to capture it. His drawing stands as a fitting tribute to a place that once played a lively role in the community—and reminds us just how important it is to document the everyday landmarks of our past. What happened to Paul Marshall and the other drawings he made? If anyone has any information, I would love to know.

The book mentioned about Billinghay, Lincolnshire, in 1993 is titled “Fire, Flood and Fenland Folk: Story of Billinghay Village and Its People”. It was published by Vilcom Books on September 23, 1993.

The story of The Mill Inn is, in many ways, a reflection of Billinghay itself—modest in appearance, yet rich in character and resilience. From its early connection to the South family’s mill, through the hands of innkeepers like Jabez Faulkner, John Henry Toulson, and Walter Templeman, the Mill Inn stood not only as a place of refreshment but as a quiet witness to rural life.

Wartime tribunals, wood auctions, community gatherings, Billinghay feast, and even the later presence of a fish and chip shop all unfolded around its doors, revealing how the site adapted to meet the village’s needs across generations. Though no trace of the building remains today, its memory lives on—in stories passed down through families, including mine, in old headlines, and in the faint shape of the lane that once led to its door.

Finally, as this exploration of Billinghay’s inns and their keepers comes to a close, I’m left with a deepened appreciation for the ordinary people who shaped village life in extraordinary ways. These beerhouse keepers, publicans, and families didn’t just serve ale—they sustained the social heart of the community, through war and peace, harvest and hardship.

In uncovering their stories, I’ve not only retraced the steps of the past but also had the privilege of connecting with those of you who carry these memories forward.

Thank you for sharing your recollections, photographs, and kind encouragement along the way. Though the buildings may now be gone or altered, their spirit endures in our stories—and as long as we continue to tell them, Billinghay’s past will never be truly lost.

Thank you for joining me on this journey—I hope you’ve enjoyed these stories as much as I’ve enjoyed uncovering them. I look forward to sharing the next chapter with you soon.

As always, if you can share any old photos or stories about The Mill Inn with me or have any connections, I would love to hear from you. Please comment here or email jackocats2@gmail.com