Following my recent posts on Billinghay’s hostelries—those lively, social cornerstones of village life—I turn now to another vital institution: The Post Office. Unlike the inns and public houses that brought the community together around hearth and ale, the Post Office quietly reshaped how people in rural Billinghay connected with the world beyond.

My late father left behind a collection of personal archives—his own memories carefully recorded. A Billinghay man through and through, he took the time to set down his recollections of village life. These notes have enabled me to build upon his legacy and bring many of these stories to light. In his records, he identifies the Post Office at the end of the road.

The arrival of the Post Office in rural villages like Billinghay marked a quiet but profound change, replacing reliance on travellers’ tales with regular, reliable correspondence that could reach miles away in just days. Often starting as a counter in a shop or a room in a private home, the Post Office was typically combined with another business, and the postmaster or postmistress became a trusted figure, handling everything from joyful birth announcements and holiday postcards to solemn telegrams bearing ill news.

The beginnings of the Post Office

It is remarkable to think that post offices have been part of English life since 1516, when King Henry VIII established the Royal Mail for official use, later opened to the public by King Charles I in 1635. In those early years, letters travelled via ‘post stages,’ where fresh horses and riders kept the mail moving swiftly—a communication revolution that would, in time, extend even to the smallest rural villages.

Victorian postmen’s uniforms and the postal service evolved throughout the era. Postmen were often nicknamed “Robins” due to their bright red jackets. The Royal Mail initially had a mail coach guard uniform in 1784, then a postman’s uniform in 1793, featuring scarlet coats. The introduction of the Penny Black postage stamp in 1840, along with Rowland Hill’s postal reforms, made the postal service more accessible. Mail delivery became more frequent, with some areas even delivering 12 times a day in Victorian London. Christmas deliveries were also a significant part of the postal service during this time.

Billinghay Post Office

The earliest documentary reference to the Billinghay Post Office appears in the 1851 Census of England and Wales, wherein Elizabeth Porter Gilbert, daughter of Francis Gilbert, is enumerated as Post Mistress. At that time, the household resided on Middle Street, Billinghay—later renamed Victoria Street—where her father, Francis Gilbert, was recorded as a draper, grocer, and farmer of 46 acres, a considerable holding for the period. The family’s financial standing is further demonstrated by the employment of a domestic servant, a marker of relative comfort and social status in a rural community. Elizabeth’s designation as Post Mistress suggests that the post office was most likely conducted from the family residence or adjoining commercial premises, a practice that was common in rural communities during the mid-nineteenth century.

On 15 July 1854, Elizabeth Porter Gilbert, born in 1833, married William Clark Atchinson, who was born in 1830. By the mid-1850s, William and Elizabeth emigrated to Australia and had their family. Following Williams’ death in 1865 in Australia, Elizabeth returned to Billinghay with her children.

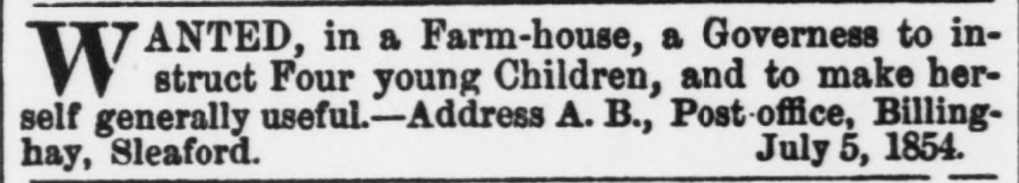

The next record I found is in the Stamford Mercury 7 July 1854– an advert for a governess – it asks any interested persons to contact the Post Office, Billinghay.

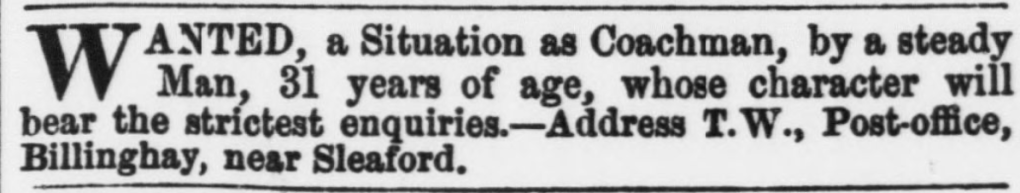

These adverts in the Stamford Mercury, 28 July 1954, illustrate that the Billinghay Post Office acted as a mail drop and collection point for personal employment inquiries, much like a recruitment agency would today—particularly helpful in an era before telephone or formal agencies.

The 1856 Gazetteer of Lincolnshire. Billinghay, stating – “The village has a Post Office, a Fire Engine, and an Association for the Prosecution of Felons“. Just for the record, the Association for the Prosecution of Felons was a voluntary local organisation formed primarily in rural parts of Britain during the 18th and 19th centuries. These associations were community-based crime-fighting groups established before the existence of organised police forces, and their purpose was to deter crime and ensure justice in their locality.

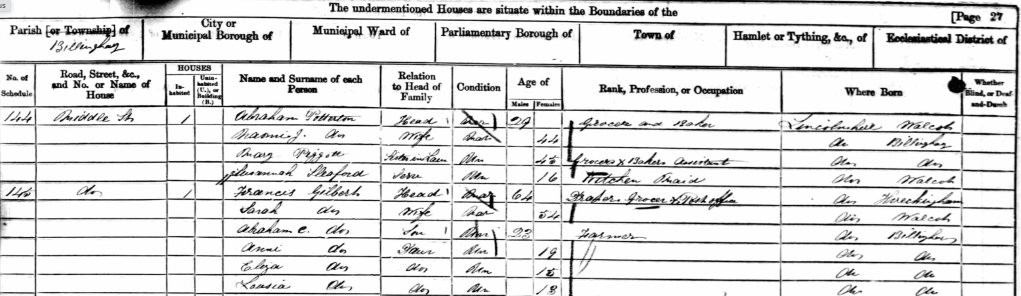

The 1856 Gazetteer of Lincolnshire: Billinghay confirms – the Post Office was still being run by Francis Gilbert with letters sent via Sleaford. The 1861 census records Francis living on Middle Street – he was a draper, grocer and post office. Francis was married to Sarah, and they had 4 children.

By the time of the 1861 Census, Francis Gilbert himself is listed as the postmaster, living on Middle Street with his wife, Sarah, and their four children. His occupations are noted as draper, grocer, and post office keeper—a testament to the multi-faceted nature of village entrepreneurship in Victorian England.

The Gilberts clearly served as the first known custodians of the Billinghay Post Office, operating it for at least a decade and likely longer. A search on Ancestry.com. UK, Poll Books and Electoral Registers, 1538-1893 – Gilbert Francis, in 1838, was living on Middle Street; he had a freehold house and land; this is where he opened his business.

1868. Francis was recorded in the Post Office Directory: Post & Money Order Office & Post office Savings Bank. Francis Gilbert, receiver. Letters arrive from Sleaford at 11.30am, dispatched at 3pm.

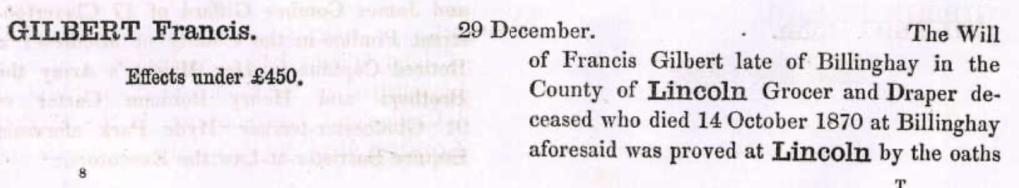

Francis Gilbert was born in 1797 in Threekingham, Lincolnshire, and died on 14 October 1870 in Billinghay. His entry in the probate records.

Following the death of her father, Francis Gilbert, the 1871 Census records that the widow Elizabeth P. Atchinson had become the new Post Mistress. Although the precise location of the post office at that date is not specified, it may reasonably be assumed that it remained on Victoria Street. Residing with Elizabeth were her three children—Charles, Gilbert, and Laura—all of whom had been born in Victoria, Australia.

Thus began a new era for the Billinghay Post Office, with Elizabeth serving as Post Mistress for the next eighteen years.

By 1872, White’s Directory locates the Post Office at the residence of Mrs. Atchinson. Letters arrived daily at 10:30 a.m. and were dispatched at 3:00 p.m. via Sleaford. In addition to its postal functions, the office also served as a Money Order Office and Savings Bank.

In 1876, Kelly’s Directory describes the establishment in more expansive terms as a Post, Money Order, Telegraph Office, and Savings Bank, with Mrs. Elizabeth Porter Atchinson named as receiver. Postal schedules remained unchanged, with letters continuing to arrive from Sleaford at 10:30 a.m. and depart at 3:00 p.m.

The 1881 Census finds Mrs. Atchinson, still active as Post Mistress, while also recorded as a draper and grocer. In 1882, White’s Directory confirms her continued service, describing the Post Office as a Post, Money Order and Telegraph Office, and Savings Bank situated at her premises. Letters arrived at 10:30 a.m. and were dispatched at 2:55 p.m. via Sleaford. Additionally, a receiving office was noted at the residence of Mr. L. Tyson, The Dales, from which letters were dispatched at 3:30 p.m. via Coningsby and Boston.

By 1885, Kelly’s Directory maintains a similar description of the office, with Mrs. Atchinson as receiver. The schedule had altered slightly, with letters now arriving at 10:45 a.m. and dispatched at 2:55 p.m., while the Parcel Post closed at 2:30 p.m.

A significant transition took place in 1889, when Kelly’s Directory lists Charles Edward Atchinson, oldest son of Elizabeth, as the receiver. By this date the office was styled as a Post, Money Order and Telegraph Office, Savings Bank, and Annuity and Insurance Office, reflecting its expanded functions within the community.

The postal arrangements had also changed: letters now arrived from Lincoln at 8:30 a.m. and were dispatched at 5:10 p.m., with the Parcel Post closing at the same hour.

The 1891 Census provides further confirmation of these arrangements and of Charles’s position at the head of the Post Office. He was now established running the PO with his wife Betsy.

1892. Kelly’s Directory. Post. M. O. & T. O., S.B. & Annuity & Insurance Office. Charles Edward Atchinson, receiver. Letters arrive from Lincoln at 8.30am. Dispatched at 5.25pm. Parcel Post closes 5.10pm.

1896. Kelly’s Directory. Post. M. O. & T. O., T. M. O, Express Delivery, S. B. & Annuity & Insurance Office. Charles Edward Atchinson, sub-postmaster. Letters arrive from Lincoln at 8.30am. Dispatched at 5.25pm.

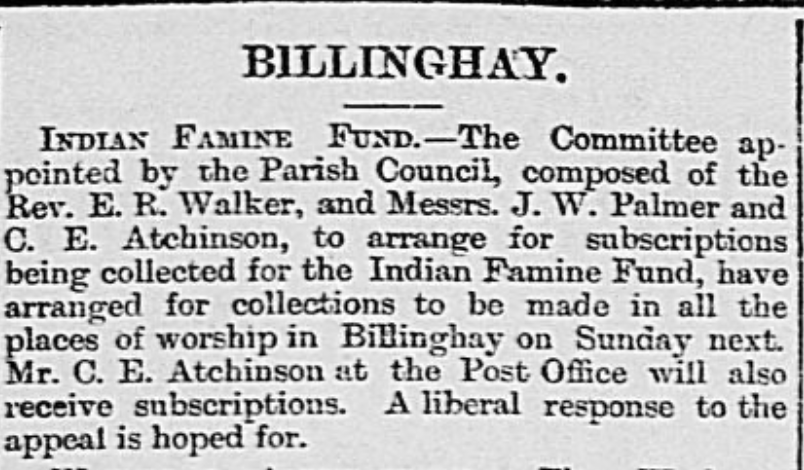

Who knew that India was experiencing a famine in 1897?

I know I didn’t, a small notice in the Lincolnshire Echo of 10 March 1897 reported that the Billinghay Post Office would begin collecting donations for the Indian Famine Fund. The famine—now recognised as part of the Indian famine of 1896–1897—was caused by monsoon failure and exacerbated by colonial policies, leaving millions in British India facing starvation and disease. Relief efforts were launched across the empire, and through the Post Office, even rural communities like Billinghay were drawn into these global networks of communication and compassion.

1900. Kelly’s Directory. Post. M. O. & T. O., T. M. O, Express Delivery, Parcel Post, S. B. & Annuity & Insurance Office. Charles Edward Atchinson, sub-postmaster. Letters arrive from Lincoln at 8.00am. Dispatched at 5.25pm.

1901. Census – confirms Elizabeth P Atchinson was a widow and living on her own means, whilst her son Charles Edward, with his wife Betsy, was running the PO. Elizabeth is now living her retirement out at the Post Office.

1905. Kelly’s Directory. Post. M. O. & T. O., T. M. O., E. D., P. P., S. B. & A., & I. Office. Charles Edward Atchinson, sub-postmaster. Letters arrive from Lincoln at 8.00am. Dispatched at 5.25pm for Lincoln; delivery at North Kyme, 5.55pm; South Kyme, 6.40, Lincoln & local letters; No delivery of letters on Sunday.

1909. Kelly’s Directory. Post. M. O. & T., S. B. & A. & I. Office. Charles Edward Atchinson, sub-postmaster. Letters arrive from Lincoln at 8.00am, 12.20pm & 5.35pm; Dispatched at 10.10am & 5.25pm for Lincoln; Delivery at North Kyme 5.55pm; South Kyme 6.40pm, Lincoln & local letters; no delivery of letters on a Sunday.

The 1911 census confirms retired postmistress Elizabeth had relocated to Nottingham to live with her married daughter, Laura. Elizabeth Porter Atchinson died in Nottingham in 1917.

1913. Kelly’s Directory. Post. M. O. & T office. Charles Edward Atchinson, sub-postmaster. Letters arrive from Lincoln at 8.00am, 12.20pm & 5.35pm; Dispatched at 10.10am & 5.25pm for Lincoln; Delivery at North Kyme 5.55pm; South Kyme 6.40pm, Lincoln & local letters; no delivery of letters on a Sunday.

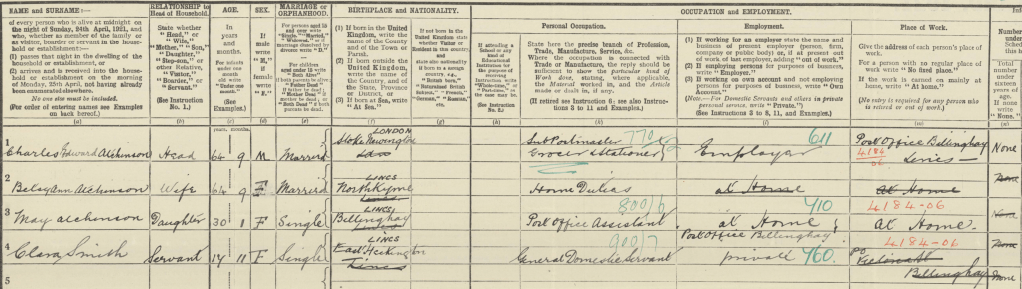

1921. Census.- Charles Edward F. Atchinson, together with his wife Betsy and their daughter Mary, resided at the Post Office on Victoria Street. Charles was recorded as the Sub-Postmaster, grocer and stationer. Their daughter, Mary, assisted in the running of the Post Office. Also in the household was a servant, 17-year-old Clara Smith from East Heckington.

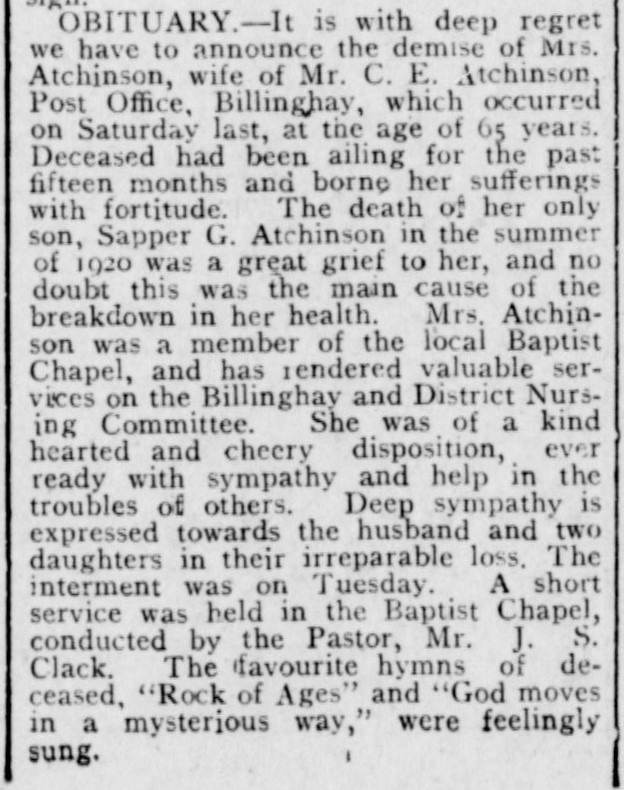

A family tragedy occurred in February 1922 when Betsy Atchinson passed away. Her death was reported in the Lincoln Leader and County Advertiser on 18 February 1922.

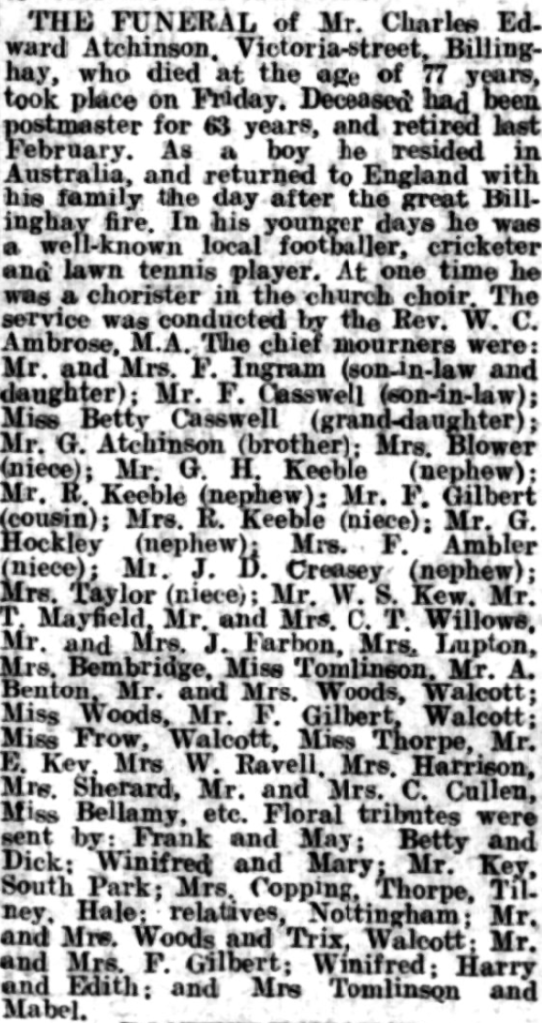

By 1934, following the retirement of her father, Charles Edward Atchinson, in February 1932, his daughter, May (Mary) Ingram, now married, assumed responsibility for the Post Office, ensuring that the family connection with its management continued into a new generation. Born 3 May 1881 in Billinghay, May (née Atchinson) was already well acquainted with the work, having served as a post office assistant to her father. The following year, in October 1933, after his retirement, Charles passed away.

In the 1939 Register, May Ingram was recorded as the Sub-Postmistress & Grocer on Victoria Street, Billinghay. Her husband, Frank Ingram, was employed by the Ministry of Labour as a clerk. May Ingram died aged 70 on 14 Aug 1961; she is buried in Billinghay cemetery. Her death was reported in the Sleaford Standard, 18 Aug 1961, and offers an insight into her life as a postmistress.

Another newspaper entry on May Ingram’s death headlines how her death severs four generations of the Gilbert / Atchinsons family running the post office from 1851 – 1961, a period of 110 years.

May and Frank Ingram never had any children. By her will, Mrs. Ingram bequeathed her share and interest in the firm of F. and M. Ingram, which was carried on at the above address, to her husband. Subject to some small bequests, the residue of her property was also left to her husband and to her niece, Betty J. Benson.

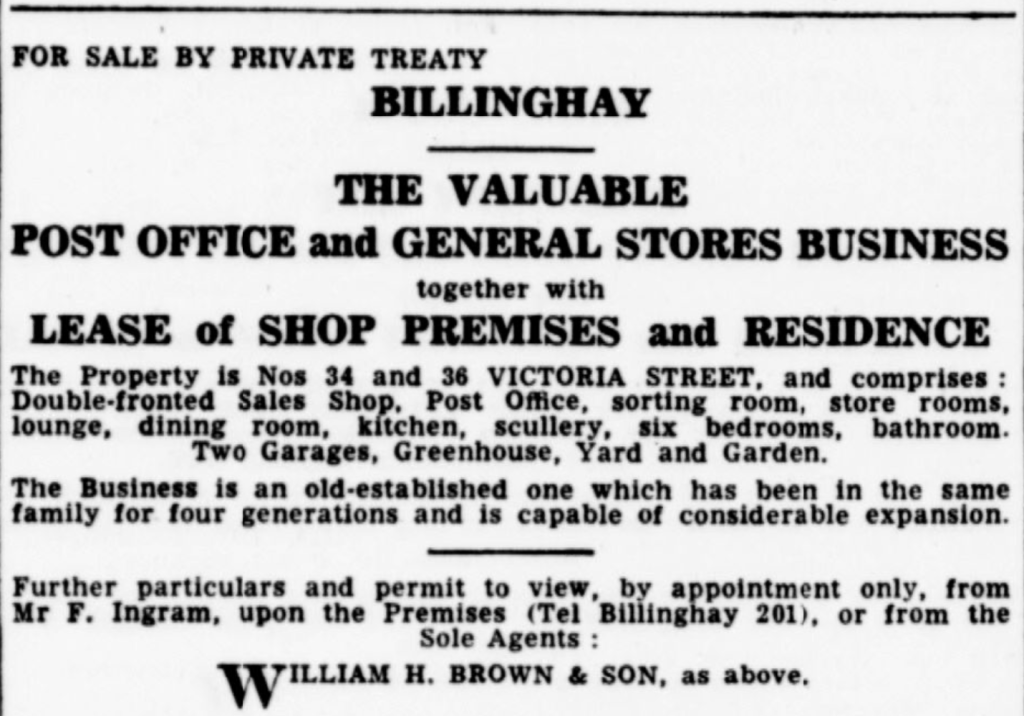

1968 -Frank Ingram put the Post Office up for sale, an advert in the Lincolnshire Standard & Boston Guardian, 21 June 1968.

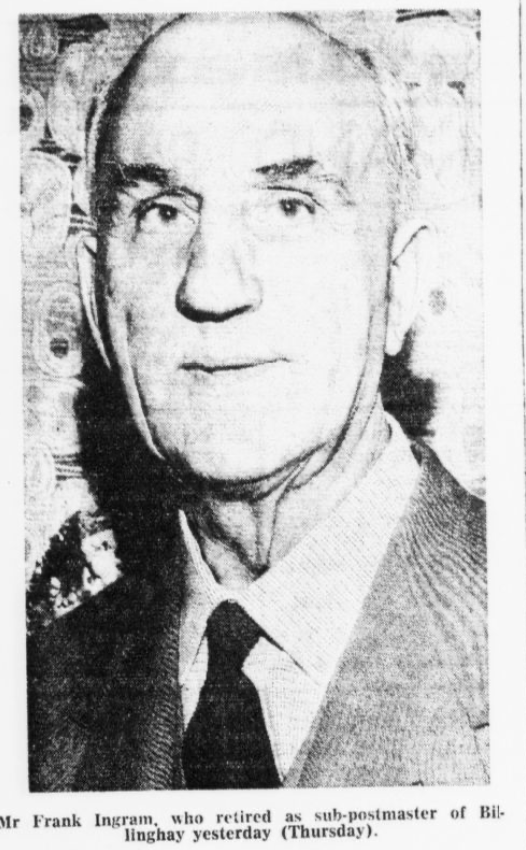

Frank Ingram continued to run the post office until his retirement in October 1968, as reported in the Sleaford Standard 1 November 1968.

By December 1968, the property was purchased by Mr. Tom Faulkner and his wife, Mrs. Phyllis Faulkner. Well known in the village, they were acquainted with the Ingram family and were appointed as Sub-Postmaster and Sub-Postmistress. Records confirm that the Faulkners remained in post in 1978. During this period they undoubtedly served me on many occasions during my frequent visits and stays in the village.

In 1986, the Billinghay Post Office passed into new hands when Barry Pearson and his wife, Jenny, became Sub-Postmaster and Sub-Postmistress. Their arrival was marked by an eye-catching advertisement in the Sleaford Standard, which invited villagers to inspect their range of goods and services and offered thanks to their growing number of customers. The notice also highlighted the wider role of the Post Office Stores on Victoria Street as both a postal service and a supplier of everyday necessities for the community.

By 1998, the future of the village Post Office had become increasingly uncertain. In an article published in the Sleaford Standard on 1 October 1998, it was reported that proposals by Royal Mail to remove the sorting and delivery function from a number of rural sub-post offices placed their survival at risk. Douglas Hogg, Member of Parliament for Sleaford, voiced his concerns to the Secretary of State for Trade and Industry, stressing that the loss of such income would undermine the economic viability of village post offices. Among those identified as being under threat of closure was Billinghay Post Office.

Conclusion: The Story of Billinghay Post Office

The story of Billinghay Post Office reflects both village life and the wider pressures faced by rural communities throughout the twentieth century.

Thus, the history of Billinghay Post Office is marked by both steadfast service and the constant need to adapt to wider economic and political pressures. From the Atchinsons and Ingrams, through the Faulkners and into the care of Barry and Jenny, the Post Office on Victoria Street has stood as a cornerstone of village life, its fortunes reflecting the resilience of the community it served. Today, the Post Office is no longer at Victoria Street; it is now integrated into the Lincolnshire Co-op hub on Church Street.

As always, if you can share any old photos or stories about The Post Office with me or have any connections, I would love to hear from you. Please comment here or email jackocats2@gmail.com