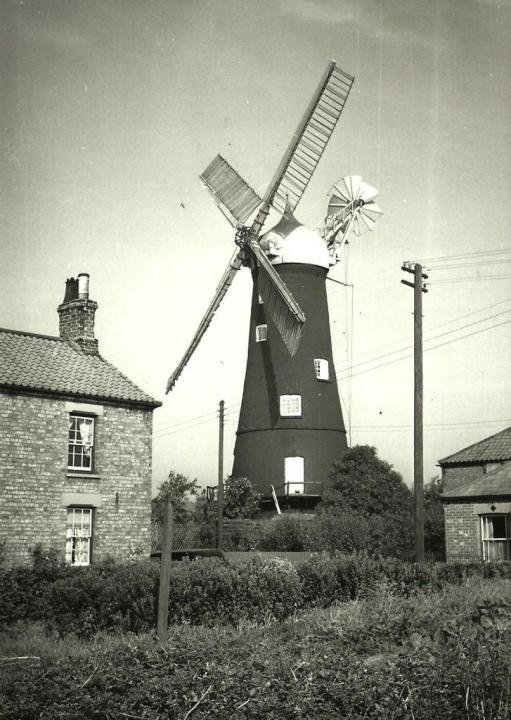

Another addition to my Billinghay postcard collection, this card initially appealed to me for reasons I did not fully recognise at the time. I was drawn to the grandeur of the mill itself, its tall tower dominating the scene, and to the familiarity of a structure whose existence I already knew, even if I did not yet understand its story. Wanting simply to add it to my collection felt reason enough.

The Mill Preserved in a Postcard.

The sepia image of Billinghay Mill on this old postcard captures a structure that once dominated the village skyline with quiet authority. Tall, weathered, and unmistakably proud, the mill was a familiar landmark to generations of local families. Today, all that remains are memories, scattered records, and rare glimpses like this photograph, preserved by chance on a postcard sent in 1911.

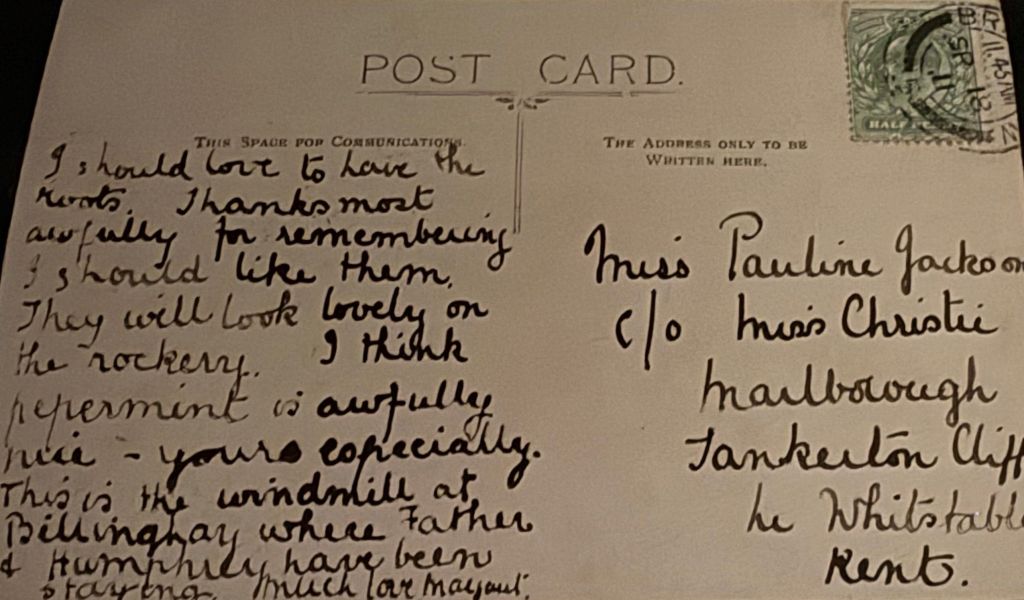

On the reverse, the looping handwriting brings the scene to life again. A simple message, addressed to a young woman in Kent, mentions the windmill at Billinghay as casually as one might refer to a neighbour’s house. In just a few lines, the writer anchors the mill in both place and family, offering a personal thread that links the past to the present.

The initial aim of this blog was to identify the sender and recipient, to establish how they came to be staying at Billinghay Mill, and to determine their connection to the family who ran the mill. However, the investigation did not unfold quite as I had expected. This postcard nevertheless provides a rare and evocative starting point.

This postcard was posted on 18 September 1911 and addressed to:

Miss Pauline Jackson

c/o Miss Christie

Marlborough

Tankerton Cliffs

nr Whitstable

Kent.

The card was sent by Margaret and reads:

I should love to have the herbs

Thanks most awfully for remembering

I should like them.

They will look lovely on the rockery. I think

peppermint is awfully nice – yours especially.

This is the windmill at

Billinghay where Father

& Humphrey have been

staying. Much love, Margaret

So I embarked on my mission to uncover the people behind this postcard.

Who were Father and Humphrey, and why were they staying at the mill?

Who was the miller at the time this photograph was taken?

And who exactly was Pauline Jackson, the young woman receiving the card at Tankerton Cliffs? The questions multiplied quickly.

Were these individuals connected to one another? Were any of them related to the owners or workers of Billinghay Mill?

I will answer these questions later.

John Edward South. The Miller.

The postcard was dated 1911, so I began by searching the 1911 Census for Billinghay in the hope of uncovering clues about the visitors, Margaret and Humphrey. Although no definitive trace of them emerged, the census did confirm the occupant of the mill: John Edward South. He was living there with his wife, Sarah Ellen Leedale, and their five children.

John Edward South was born in Billinghay, December 1851, the son of Edward South and Sophia Lowe. Edward worked as a wheelwright, but his early death in 1855 left Sophia widowed with a young son to raise alone.

By 1871, John Edward had established himself as a baker. A decade later, in 1881, he appears in the records as both miller and baker, operating the mill on Victoria Street, Billinghay. It was at this point that my curiosity shifted away from the visiting family and towards the setting itself. What, exactly, was the story of the mill, and how long had it stood at the heart of the village?

The South Mill History

A Historical Overview.

South’s Mill, also known as Black Tower Mill or East Mill, was constructed around 1806 on the site of an earlier post mill on Victoria Street, Billinghay. The replacement of the wooden post mill with a brick tower mill reflects a broader early nineteenth century shift in rural Lincolnshire towards more permanent, durable, and powerful milling structures. Such developments were driven by advances in milling technology and a growing demand for efficiency, signalling both economic confidence and long-term investment in local industry.

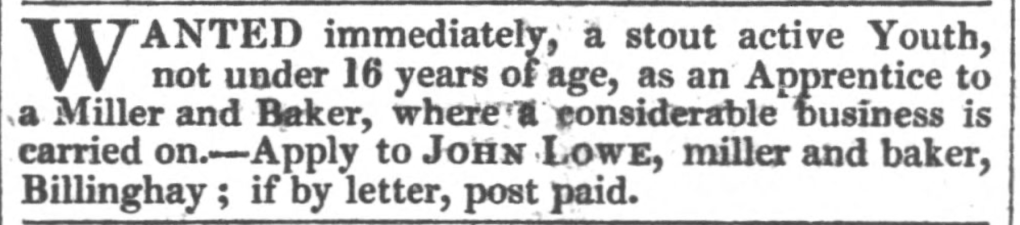

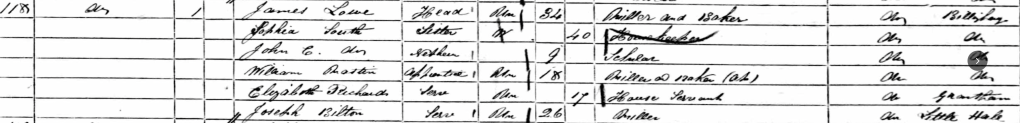

By 1829, a newspaper advertisement confirms that the mill was being operated by John Lowe, and the 1841 census further establishes that he was still in occupation at that time. This places Lowe among the earliest known long-term operators of the tower mill and firmly puts him in charge during its formative decades.

In 1830, the mill was substantially rebuilt and raised by two additional storeys following storm damage, transforming it into a far larger and more productive structure. Ultimately, it developed into a seven-storey tower mill—one of the most prominent industrial landmarks in Billinghay.

Although the mill later became universally known as South’s Mill, the early evidence confirms it was originally associated with the Lowe family.

By the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the mill was firmly established as a South family enterprise, and it was under this name that it entered both local memory and the historical record.

The mill continued to operate into the early twentieth century but finally ceased working in the 1930s. The upper structure was later dismantled or lost, leaving only the brick stump that survived until recently as one of the last visible remnants of Billinghay’s milling past.

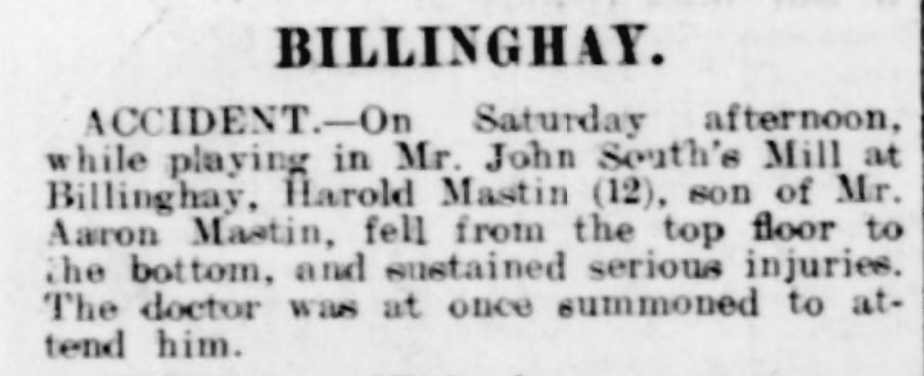

An Accident at South’s Mill: The Case of Harold Mastin.

Despite its picturesque appearance, South’s Mill was a dangerous place of work. Windmills contained exposed shafts, gears, and drive belts, with little in the way of safety protection. In 1913, only two years after the postcard was posted, a terrible accident occurred when twelve-year-old Harold Mastin was killed while working at the mill. He had become entangled in the machinery. The incident was widely reported at the time and became part of local memory. I recall my father telling me the story. It stands as a stark reminder that behind the tranquil postcard image lies a hazardous and unforgiving industrial environment.

The incident was recorded in the Lincoln Leader & County Advertiser.

Ownership.

When my focus turned to how the mill passed into the hands of the South family, it became clear that the story begins before the tower mill itself was constructed. Before the erection of the brick tower mill around 1806, the site on Victoria Street was occupied by an earlier post mill. The ownership of this earlier wooden mill is unknown, and I have not to date located any documented evidence.

This lack of clarity is not unusual. Post mills were frequently rebuilt, replaced, or relocated, and their ownership often shifted between millers, landlords, and local investors. In many cases, the individual operating a mill was not the freeholder of either the land or the structure itself, but a tenant working under a lease or agreement. As a result, names associated with a working mill can change without leaving a clear paper trail, particularly in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. So I turned my attention to understanding how John E South became the local miller.

The following two photos were found on the Society for Lincolnshire History and Archaeology website: Society for Lincolnshire History & Archaeology

I now knew that John Lowe was the first clearly identifiable occupant of the tower mill. He appears again in the 1851 census, where he is recorded as living in Middle Street, Billinghay, and described as a “miller and baker employing four men.” This entry confirms that by the mid-nineteenth century, the tower mill was operating as a substantial commercial enterprise, with a defined workforce and an associated baking business.

The scale implied by this census return corresponds closely with the enlarged seven-storey mill that had emerged following the rebuilding of 1830. Taken together, the documentary evidence strongly indicates that Lowe was operating the tower mill on Victoria Street.

John Lowe was born in 1895 in Gedney, Lincolnshire, and was married to Elizabeth. Census records show that by 1861, John Lowe had retired from work and was living on his own means in King’s Lynn. So who took the mill over?

A search of the 1861 census provides a crucial connection between the Lowe and South families. In 1861, the mill was being run by James Lowe, who was the son of the now-retired John Lowe, confirming the continuation of the Lowe family’s involvement into the second generation. Living in the same household was his sister, Sophia South, née Lowe. Sophia was the widowed wife of Edward South, the wheelwright.

Also residing with them was nine-year-old John Edward South Sophia’s son and James Lowe’s nephew. His presence in the miller’s household is highly significant, as it places the future miller directly within the working environment of the mill from childhood. This arrangement strongly suggests early exposure to the trade and reinforces the idea of an organic, family-based transfer of knowledge and responsibility.

Unsurprisingly, the young John Edward South would later become the miller himself, continuing in that role until he died in 1929.

By 1871, John Edward South was still living with his uncle, James Lowe, at the mill and was recorded in the census as a baker. Confirming his continued involvement in the family business during his early adult years. By 1881, however, James Lowe had left the mill and was now recorded as a farmer in Billinghay; James died in 1905.

In that same year, 1881, the mill was now being run by his nephew, John Edward South, who appears in the census described as both miller and baker. This marks the clear point at which operational control of the mill passed from the Lowe family to the South family.

Taken together, the census evidence provides firm documentary proof that the mill transferred through marriage and inheritance rather than by purchase.

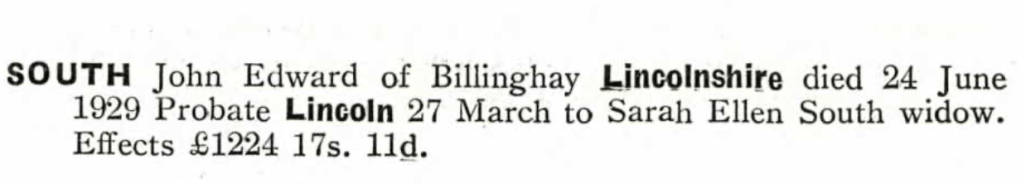

By 1921, John Edward South and his wife, Sarah, now in their late sixties, were still living at the mill. John Edward South died on 24 June 1929 in Billinghay, and with his death, the working life of the mill effectively came to an end, closing a chapter that had spanned more than a century of continuous family operation.

The South family entered the business as part of an established family enterprise, and their long tenure as both operators and occupants ensured that the mill became known locally and historically as South’s Mill.

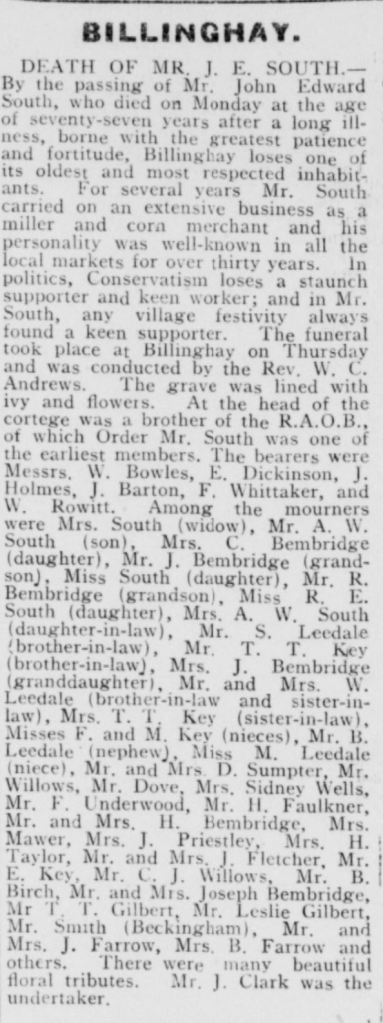

John Edward South’s death was reported in the Lincoln Leader and County Advertiser on 29 June 1929, and the obituary provides a vivid insight into his standing within the community of Billinghay. Described as one of the village’s “oldest and most respected inhabitants,” South is presented not merely as a tradesman but as a central and well-known figure in local life.

The notice records that for many years he carried on an extensive business as a miller and corn merchant, and that his personality was familiar in local markets for over thirty years. This confirms the scale and reach of his commercial activity and reinforces the documentary picture already established through census evidence.

Beyond his business interests, the obituary emphasises his civic engagement. Described as a staunch Conservative supporter and a keen worker, and it notes that village festivities “always found a keen supporter” in him. His membership of the Royal Antediluvian Order of Buffaloes, of which he was one of the earliest members locally.

The Royal Antediluvian Order of Buffaloes (RAOB), known as the “Buffs,” is one of the largest, non political and non religious fraternal / charitable organisations in the UK, founded in 1822. It provides social support, friendship, and charitable grants for illness, disability, and education to members and their families, with a motto of “No Man Is At All Times Wise”

The lengthy list of mourners, drawn from family, extended kin, and the wider community, reflects both his personal connections and the respect in which he was held. With his death on 24 June 1929, Billinghay lost not only its long-serving miller but a figure whose identity had become closely intertwined with the mill, the market, and the life of the village. In practical terms, his passing also marked the end of the working life of South’s Mill.

Today, virtually nothing remains of South’s Mill beyond the truncated brick stump that still marks its former position in Billinghay. This modest remnant lies in the history of a substantial family enterprise that began with John Lowe in the early nineteenth century, expanded under his son James, and passed through marriage to John E South.

The 1911 postcard captures the mill in the final decades of its working life, standing at the end of a lineage of millers stretching across four generations.

The People behind the Postcard.

So I return to my initial mission to uncover the people behind this postcard. So, recapping on my original questions. Who were Father and Humphrey, and why were they staying at the mill? Who was the miller at the time this photograph was taken? And who exactly was Pauline Jackson, the young woman receiving the card at Tankerton Cliffs? Were these individuals connected to one another? Were any of them related to the owners or workers of Billinghay Mill?

What the Postcard Reveals — and Conceals.

This investigation began with a single postcard and a handful of names, offering only a few clues. Through census records, newspapers, and family connections, it has been possible to reconstruct the history of the mill with considerable confidence.

In this respect, the postcard has fulfilled one of its most important roles: it has anchored an image to a specific place, family, and moment in time, transforming a casual piece of correspondence into a document of local historical value.

Yet Margaret, Father and Humphrey remain unidentified, and Pauline Jackson, the postcard’s recipient in Whitstable, remains outside the known genealogical and business networks of Billinghay. The postcard hints at South’s Mill as a lived-in, social space, not merely an industrial workplace, but a household open to visitors, correspondence, and connections that extended well beyond the village.

The postcard has not surrendered all its secrets, but it has given enough to place it firmly within the story of the mill, the South family, and the wider life of the village. That balance between certainty and mystery is, perhaps, where its true historical value lies.

Unless, of course, someone out there knows who the visitors were and any possible connections?

Personal memories.

As a young child, I visited Billinghay often during the school holidays, staying with family in the village. I remember regularly walking past the ivy-clad stump of the mill, always fascinated by it, though at the time I knew nothing of its history or significance.

My paternal family has deep roots in Billinghay, and my father was born in Billinghay Dales, shaped by the same landscape that had once sustained the mill and the community around it. Looking back now, it feels as though this research was less about uncovering the history of a forgotten building and more about rediscovering a place that had quietly formed part of my own story all along. So the next time I walk past the spot where Souths Mill once proudly stood, it will no longer feel anonymous,

And Finally……

And yet, even this story was not quite finished, as John Edward South’s father, Edward South, was a wheelwright, and in the 1851 census, a young man by the name of Joseph Holmes was an apprentice to Edward. Surprise! Joseph Holmes is my great-uncle x2. Quite by accident and entirely unbeknownst to me myself once again connected to the very people I thought I was merely researching. As soon as I saw the surname of Holmes, I just knew there would be a connection!

It is a familiar pattern. Just by searching for a piece of local history, it turns out to be standing rather closer to home. One begins to suspect that the past is not so much being discovered as quietly tapping one on the shoulder, with a wry smile, saying, you’re part of this too!

As always, if you can share any old photos or stories about the Lowe or South Family or The Mill at Billinghay with me or have any connections, especially to the Postcard recipient or writer, I would love to hear from you. Please comment here or email jackocats2@gmail.com